Defining mental wellbeing in a post-pandemic world.

21 September, 2020.

Table of Contents

Mental Health in the time of COVID-19

2020 has been a massive year for change, uncertainty, and disruption. Despite learnings that have accompanied over 30 million recorded cases of COVID-19 there are still more unknowns than knowns. As 90% of the human population heads into colder months, one pressing question is: will colder weather favour the virus, as it does the flu1,2?

Early in the pandemic, on 14 May 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) stated “The impact of the pandemic on people’s mental health is already extremely concerning,” and “social isolation, fear of contagion, and loss of family members is compounded by the distress caused by loss of income and often employment.3”

Fast-forward to the present time and mental health is more important now than ever. As Mental Health Awareness Week kicks off in New Zealand perhaps the first question we need to be answering is: what is mental health, and what (if anything) does it mean today?

In this article you will see that the idea of ‘mental health’ is ill-defined and misunderstood. You will learn about a really useful and empowering way to talk about ‘mental health’ in terms of illness and wellbeing. Finally you see that mental wellbeing has an important protective effect that boosts quality of life and can suppress symptoms of mental illness.

Why do we say 'Mental Health'?

Despite mental health and wellbeing holding such central importance in 2020, the terms have historically been poorly defined or misunderstood. Even the majority of western psychologists hadn’t begun to properly define what the phrase ‘mental health’ meant until quite recently 4.

From the 1950’s until the mid-2000s the state of ‘mental health’ was simply summed up as ‘an absence of mental illness’4. It was a binary definition that you were either a) mentally ill, or b) mentally healthy, without much room in between. This was very straightforward thinking and even today it seems to makes sense at first glance, in part because the language being used, e.g. mentally ‘healthy’ vs. ‘ill’, is deceiving.

One reason for the choice of words was that mental illnesses (psychopathology) were studied earlier and in more depth than mental health5,6; which is why it was included under the umbrella, and defined as the antithesis, of illness.

This oppositional definition created a set of assumptions. Firstly, a person couldn’t be simultaneously mentally ill and mentally healthy. Secondly, all mentally healthy people were reasonably uniformly functional, and more functional than the mentally ill. Under this model people were expected to fit into one of two groups that occupied opposite ends of the same mental scale: healthy or ill, with little variation and no crossover.

Thankfully this old but enduring model of mental health is evidently wrong and it is easy for you to think of obvious real-world situations that don’t fit:

- ‘Mentally healthy’ people aren’t all equally functional or even equally healthy.

- Some people with ‘mental illness’ are frequently super functional and productive; e.g. Beethoven, Silvia Plath, Mariah Carey, and Kanye West.

- You don’t need to have clinical depression to be depressed.

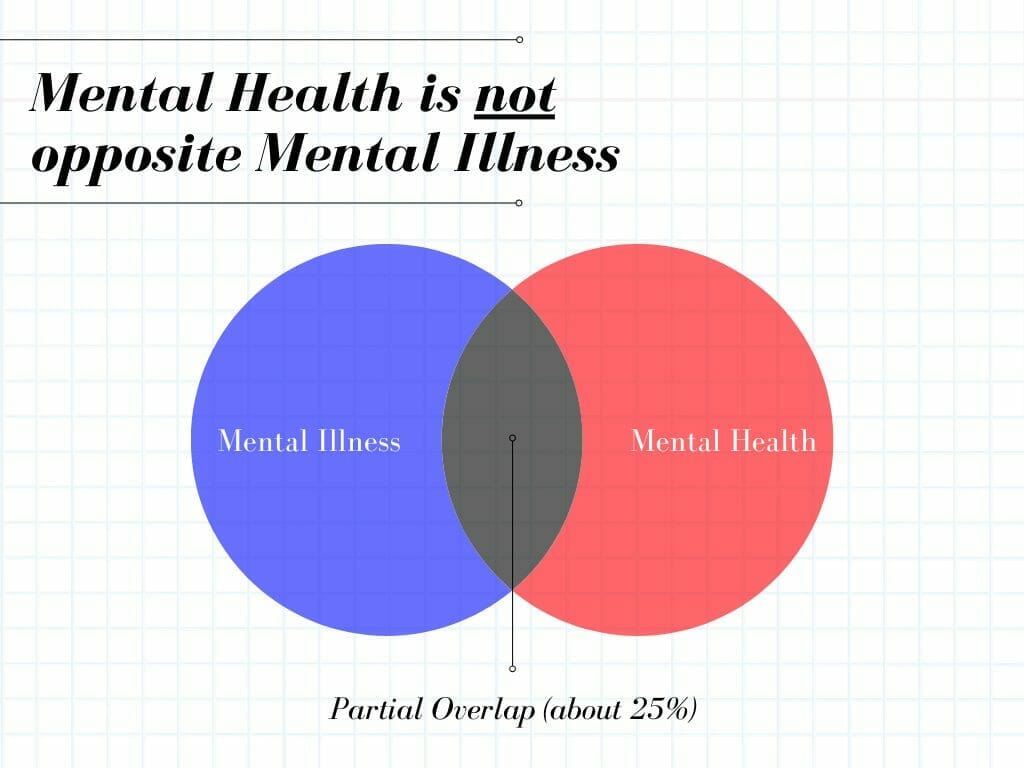

Mental Health is not the opposite of Mental Illness

In 2005 a psychologist and sociologist by name of Corey Keyes began exploring this question by creating a more flexible model of mental health and testing it4.

Basically, he expanded the binary ‘healthy vs. ill’ model from the 1950’s to fit better with real life. His new model kept the categories of ‘ill’ and ‘not-ill’ but added levels to them that represented low, moderate, or high mental functioning. In other words, the state of mental illness was effectively separated from the state of mental functioning. This new model was tested with a bunch of people (about 7000) and this is what was found:

Mental health was not the opposite of mental illness! In fact, what defines mental illness only overlaps with about a quarter of what defines mental health. The two things are related, but mostly different; mental health is the cousin of mental illness. With this more accurate model it is even possible to have a mental illness and be simultaneously mentally healthy.

In terms of language use Dr. Keyes used the terms ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ but also adding three adjectives to describe psychosocial functioning: ‘flourishing’ for high functioning, ‘moderate’ for moderate, and ‘languishing’ for low functioning. Unfortunately these terms never really caught on and in 2020 many people still think and talk in terms of health vs. illness.

It is clearly very useful to know about ‘flourishing’ or ‘languising’ ‘psychosocial functioning’ but the language is very dense and academic. Let’s use ‘mental wellbeing’ instead.

Health encompasses both Wellbeing and Illness

The idea of ‘mentally healthy vs. ill’ is outdated, incorrect, and disempowering regardless of which label you currently have.

Remember that the term ‘mental health’ was defined to be opposite ‘mental illness’ but in reality they are not opposites but separate and overlapping dimensions of health. For this reason it makes more sense to use ‘mental health’ as a neutral term for a persons overall experience of illness and wellbeing. Just as the weather encompasses both sunshine and rain, so it is that mental health encompasses both illness and wellbeing. You can even use similar language as the weather: “my mental health is good today, I feel fine” or “I feel stormy today and my mental wellbeing is low”.

By using ‘mental wellbeing’ in combination with ‘mental illness’ we can describe a lot about experiences of mental health in a useful and balanced way. This is how I suggest we define these terms.

- Mental illness: a type of actively expressed, specific and diagnosable, medical condition affecting the mind that is typically experienced by 1 in 5 adults in a given year either temporarily or chronically. Mental illness is personal and can be treated.

- Mental wellbeing: a fortifying and empowering state, experienced in lesser or greater degree, in which an individual can realise their own abilities, cope with the challenges of everyday life, contribute meaningfully where they choose to, and feel reasonably calm and happy as befits their experience.

- Mental health: a neutral term that encompass a persons complete experience of mental illness and mental wellbeing.

Mental Illness

This means that the mental illness is currently generating negative symptoms i.e. it’s not benign or in remission. This is very important because a common misconception about mental illnesses is that they are always active. In reality a person experiences periods of illness and wellness of varying intensity. Therefore it isn’t fair to label someone who was diagnosed with a mental illness as ‘ill’ when they aren’t actually experiencing symptoms of illness. Makes sense.

This means that it can be found within the current realm of psychiatric disorders known as mental illness. If you glance at a history of mental illness you will see that for a long time simply being different was enough to be committed to an insane asylum – with all human rights revoked. During Victorian times women in particular faced terrible mistreatment from being casually declared mentally ill, infirm, hysterical, or deranged. A mental illness needs to be a specific thing with a specific treatment so that people are not manipulated or harmed simply for being not-normal (as if anyone is normal!). Being a medical condition, mental illnesses are highly confidential unless disclosed by the individual and privacy should be protected. Don’t talk about a persons illness to others without their permission. Especially in our digitally connected world, disclosing a persons illness can leave them open to anonymous abuse and persecution (plus it violates their right to privacy).

More than 50% of people will be diagnosed with a mental illness or disorder in their lifetimes and one in five people will experience mental illness in a given year. Typically illnesses are often temporary or, if long-lasting, follow periods of expression or remission.

There are ways to improve a persons capability and quality of life despite being ill and new treatments, both medical and non-medical, are always being discovered. Importantly, everyone experiences mental illness in their own way and this creates opportunities, beyond what is commonly described, to live a good life. Some people even manage to turn a mental illness into an ally.

Mental Wellbeing

Mental wellbeing increases our health, capability, and resilience. It can help protect people with mental illness from the affective symptoms of that illness4,7. In other words, mental wellbeing acts like a shield that enhances your life and protects you from stresses and illnesses of the mind (more on this in the next section).

Mental wellbeing is kind of like a resource in that you can have a lot or a little and it could be good or bad. E.g. “My mental wellbeing is good today” or “I don’t have a lot of mental wellbeing right now” or “my wellbeing feels a bit low” (of course you should use any words you like best). Generally, the more mental wellbeing the better and there are many ways to have more wellbeing e.g. exercise, mindfulness, laughing, social interaction, meaningful connections, meditation, being in flow, expressing yourself etc.

This depends on what your everyday life is like, clearly some people have much more to cope with than others, but in essence it is talking about capability; the power to manage and make change. Of course when tragedy strikes circumstances are no longer ‘everyday’ and as the pandemic continues it seems likely that more and more people will experience hardship. This is why maintaining mental wellbeing will be especially important and rewarding in coming times.

It is important to feel like what you do as a person can be meaningful. This doesn’t mean that everything you do needs to be amazing or profound, most of us face the daily grind after all, but it helps if something sparks your passion or allows you to feel part of ‘something larger’.

As an example consider the job that Albert Einstein had before he was famous. After graduating in 1900 Einstein spent two unsuccessful years looking for work as a teacher before settling for a job at a Swiss patent office in Bern, as an assistant examiner. Suffice it to say that he isn’t famous for his contributions to the world of patenting, even though he was a genius and worked there for 7 years from 1902 to 1909. It was a job to support himself, but during that time he continued to engage with science and philosophy, even using some of what he saw at the patent office as inspiration for his breakthrough ideas. He chose carefully where he wanted to make a meaningful contribution.

Everyone has good and bad days. Having high mental wellbeing doesn’t mean feeling great no-matter-what but it does help with feeling emotions that match what is happening to us, for us, and around us.

How Mental Wellbeing protects you during covid-19

Lets revisit Dr. Keyes study4 one more time to learn something very important.

During the test he found that in terms of measuring helpfulness, goals, resilience, and intimacy; it didn’t make much difference whether people were mentally ill or not ill, as long as they had ‘moderate’ or ‘flourishing’ psychosocial functioning. Translated into our language: as long as mental wellbeing was abundant, mentally ill people scored about as highly as those who were not ill. The area where there was a clear difference between ill and non-ill was at work: cutbacks and lost workdays were worse for mental illness.

It was also found that people with low mental wellbeing scored equally poorly regardless of whether or not they had an illness. In other words, having high mental wellbeing was protecting people from the negative affects of mental illness, and having low mental wellbeing was affecting people as if they had a mental illness.

I can verify this effect personally because keeping track of my own mental wellbeing is my main strategy for treating bipolar disorder. You can see two very different months from 2019 in the picture below. I have removed dates and labels, but you can still clearly see that I experienced much lower mental wellbeing in the second month.

Two important things here are the red line and the green line. I have found that so long as I stay above the green line I don’t really experience any symptoms of bipolar disorder but when I fall below the red line my bipolar starts to be expressed and I feel mentally ill. Going by this I felt fine in the first month, and terrible in the second: stressed out, couldn’t sleep properly, really depressed and hopeless. The difference between these two experiences was my level of mental wellbeing.

This effect is similar to what was reported in 20054 and the main takeaway here is: one effective thing that can be done to maintain capability, resilience, and a positive experience of life during the stresses of COVID-19 is to focus on creating a state of abundant mental wellbeing for yourself and your loved ones.

Conclusion

In conclusion ‘mental health’ has been used for decades without a clear definition and this has disadvantaged both mentally well and mentally ill people. Studies have shown that mental health is not the opposite of mental illness and what defines mental illness only overlaps with about a quarter of what defines mental health. I suggest that the term ‘mental health’ is used in a neutral way to encompass a persons complete experience of mental illness and mental wellbeing.

I propose that these definitions are the most useful:

- Mental illness: a type of actively expressed, specific and diagnosable, medical condition affecting the mind that is typically experienced by 1 in 5 adults in a given year either temporarily or chronically. Mental illness is personal and can be treated.

- Mental wellbeing: a fortifying and empowering state, experienced in lesser or greater degree, in which an individual can realise their own abilities, cope with the challenges of everyday life, contribute meaningfully where they choose to, and feel reasonably calm and happy as befits their experience.

- Mental health: a neutral term that encompass a persons complete experience of mental illness and mental wellbeing.

Mental wellbeing can have a powerful effect to boost capability, resilience, and a positive experience of life during the stresses of COVID-19. In addition, moderate to high levels of mental wellbeing can help to protect people from the symptoms of mental illness. For both of these reasons it is recommended that people explore ways to increase their mental wellbeing to create improvements for their capability and quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[1] https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/OXAN-DB255084/full/html

[2] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-18150-z

[3] https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/14-05-2020-substantial-investment-needed-to-avert-mental-health-crisis

[4] Keyes CLM: Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical psychology 2005, 73:539-54

[5] Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books.

[6] Smith, M. B. (1959). Research strategies towards a conception of positive mental health. American Psychologist, 14, 673-681.

[7] Slade, M. Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Serv Res 10, 26 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-26

The author is neither a doctor or psychologist or claims to be.

The ideas expressed in this article are not medical opinions. This article is intended to be useful and informative, not to subvert or replace medical treatments, therapies, or diagnosis. If you are experiencing undue distress please seek medical assistance.